PVTIME – The European Union has postponed revisions to its Cybersecurity Act (CSA) due to disagreements between officials and member states, a development with potential implications for the continent’s solar sector. First introduced in 2019, the CSA has recently been reassessed in response to an increasing number of cyberattacks. The findings were originally set for publication on 14 January, but reports suggest the announcement will now take place on 20 January. Disputes over the scope of the changes are said to be the cause of the delay. Solar inverters have already been classified as a high-risk supply dependency in the EU’s Economic Security Doctrine.

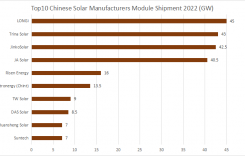

Restrictions on digital technology supply chains are expected to be at the centre of debates within the solar industry. Chinese companies dominate Europe’s solar inverter market, with Huawei, Sungrow, GoodWe and Deye being among the leading suppliers. Stricter controls on component supplies could exclude these firms from critical infrastructure projects, mirroring the tight restrictions already imposed on Huawei within the telecommunications sector. Last November, Henna Virkunnen, Executive Vice-President of the EU’s Committee on Technology and Security, noted that the CSA review would focus on strengthening the security and resilience of information and communication technology (ICT) supply chains and infrastructure.

During the review process, the European Parliament proposed adding a digital sovereignty clause to cybersecurity certification, a suggestion that has attracted opposition from some industry stakeholders and member states. The clause would require cloud services supporting European infrastructure to be hosted within the EU in order to gain certification, thereby shifting the regulatory focus from physical components to the servers and data centres that support them. Major US tech firms, including Amazon, Google and Microsoft, which have deep ties to Europe’s cloud infrastructure, have also strongly opposed this proposal, as they aim to avoid mandatory regulations that could reduce their influence.

Meanwhile, the EU’s classification of solar inverters as a high-risk supply dependency in its Economic Security Doctrine, released in December, reflects concerns over cybersecurity and the sector’s reliance on a single supplier base. For some time, industry insiders and EU officials have called for tighter restrictions on solar inverters, with the trade body SolarPower Europe urging an action plan to support domestic manufacturers as early as November 2024. The organisation has warned that the collapse of the domestic sector would result in Europe losing control of critical digital infrastructure.

The mandatory phasing out of Chinese technology in critical infrastructure could force numerous solar PV and energy storage projects to replace existing inverters, and new projects might be banned from using imported technologies. Such measures would most likely apply only to large-scale ground-mounted solar projects, as defined by the EU as assets vital to maintaining basic social functions, the disruption of which would impact at least two member states. However, imposing strict, burdensome restrictions on domestic inverter supplies could create complex political challenges.

The CSA review is evaluating potential non-technical supply chain restrictions to be enforced by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). These could include compulsory cybersecurity certification, limits on the dominance of a single supplier or country in inverter supplies, and full product recalls and replacements, similar to those imposed on Huawei’s 5G infrastructure. In a report published in June 2025, cybersecurity firm Forescout found that 76 per cent of the 35,000 internet-connected solar devices, including inverters and data loggers, surveyed globally were located in Europe. This remote access poses a key cybersecurity risk, as the linked cloud infrastructure and servers are susceptible to manipulation and attacks.

The technology-focused sovereignty proposal, which would require critical cloud infrastructure to be based within the EU, could restrict remote access. This would mean that solar projects exceeding a certain critical threshold would be unable to connect to cloud infrastructure or data centres outside the bloc. For the solar and energy storage sectors, where digital control tends to be based in Eastern Europe rather than Western Europe, the proposal carries significant weight. Rather than imposing outright supply bans, the EU could introduce a certification system that mandates the domestic hosting of critical cloud infrastructure, which would have tangible technical implications for solar projects across Europe.

While the scale of active digital threats to Europe’s renewable energy infrastructure is difficult to quantify, most experts agree that existing legislation and regulations lack adequate safeguards. European inverter manufacturers are expected to support the strictest possible restrictions, which could boost demand for their products overnight. In contrast, major Chinese firms, which have established strong roots in Europe’s solar industry and infrastructure, are pushing for a framework that is more closely aligned with standard industry practices or guidelines.

Scan the QR code to follow PVTIME official account on Wechat for latest news on PV+ES