PVTIME – In 2024, China’s photovoltaic (PV) industry experienced an unprecedented decline across its four core value chain segments: silicon materials, wafers, cells and modules. Driven by supply-demand imbalances, rampant capacity expansion and relentless price competition, these sectors experienced a year-long decline that tested the resilience of even the largest enterprises. While this crisis inflicted severe short-term losses, it also triggered a fundamental reckoning for an industry long accustomed to breakneck growth.

Silicon Material: A Relentless Price Collapse Breaching Cost Foundations

The polysilicon market in 2024 was characterised by extreme volatility, with prices spiralling downward from the outset. Starting the year on a trajectory set in late 2023, the market was shaped by a delicate balance of supply and demand that quickly tipped towards oversaturation. Dense polysilicon averaged 58,100 RMB/tonne at the beginning of the year, reclaim material averaged 60,800 RMB/tonne, and N-type material commanded a premium at 69,600 RMB/tonne. A temporary construction surge in February briefly lifted prices to annual peaks — dense silicon reached 60,100 RMB/tonne in March — but this rally proved illusory.

From April onwards, prices entered a period of freefall, driven by a combination of factors. A surge in domestic production capacity flooded the market, while overseas demand failed to keep pace, creating a supply glut that swelled inventories. By April, dense silicon had slumped to 49,600 RMB/tonne (-10,600 month-on-month), with N-type material suffering the steepest drop of 18,000 RMB/tonne to 54,100 RMB/tonne. The slide accelerated in May, with the price of most grades crashing below the 30,000 RMB threshold. Dense silicon hit 37,700 RMB/tonne, reclaim material hit 39,200 RMB/tonne and cauliflower-grade silicon hit 34,600 RMB/tonne. By June, polysilicon factory inventories had surged by 118.89% from Q1, reaching a staggering 251,500 tonnes.

Silicon wafers: Price Slashes, Inventory Woes and Technological Disruption

Despite the theoretically beneficial effect of falling silicon prices upstream, wafer manufacturers found themselves caught in a “cost-crushing” paradox that intensified losses. For firms locked into long-term silicon material contracts signed at premium prices, the crisis was doubly cruel: they had purchased raw materials at their peak value, only to see wafer prices plummet before they could process and sell their products. In January 2024, N-type G10L wafers were priced at 2.04 yuan per piece, P-type M10 wafers at 1.96 yuan per piece, and P-type G12 wafers at 2.93 yuan per piece — a seemingly stable situation.

However, the February–March period marked a turning point. While P-type M10 wafer prices increased by 0.09 yuan/piece in February, N-type G10L and P-type G12 wafer prices fell by 0.04 yuan/piece, hinting at the turmoil to come. From March onwards, the decline became relentless. By December, N-type G10L wafers had fallen by 49.18% to 1.04 yuan per piece, P-type M10 wafers had fallen by 43.97% to 1.10 yuan per piece, and P-type G12 wafers had fallen by 43.28% to 1.66 yuan per piece. This crisis was driven by two intertwined forces: rampant capacity expansion across the wafer sector flooded the market with supply, while sluggish downstream demand from PV installers was unable to absorb the surplus.

The rapid technological shift towards N-type wafers compounded the issue. As N-type technology matured, it became more cost-effective and efficient than traditional P-type wafers. This put further pressure on P-type prices and created a dual market reality: while N-type wafers gained market share, P-type manufacturers faced the risk of becoming obsolete. For wafer producers, the crisis created a Catch-22 situation: reducing prices to clear inventory only increased losses, while holding onto stockpiles resulted in substantial impairment charges as values plummeted. The sector was under significant operational pressure, with every price cut exacerbating balance sheet strain.

Solar Cells: The 0.5 Fen Divide and N-type’s Inevitable Rise

The 2024 solar cell market was characterised by technological disruption and structural upheaval. The year began with relative stability in Q1, when PERC 182 cell prices managed a slight rebound of 0.023 yuan/W in March — an early sign of changing supply and demand dynamics. However, Q2 brought a rude awakening as the average price of PERC 182 and 210 cells plummeted to around 0.3 yuan/W, aligning with TOPCon 182 cells. This price parity was a seismic event, signalling the beginning of the end for P-type technology.

The most telling metric was the negligible 0.5 fen price gap between P-type and N-type cells — a margin so slim that it made P-type technology commercially unviable in the long term. Driven by superior efficiency and rapidly falling costs, N-type cells — particularly TOPCon and HJT technologies — began to dominate. Large-size N-type cells, such as TOPCon 182×210, quickly gained favour due to their cost-reduction and performance advantages, with price differences between the 210 and 182 sizes narrowing significantly. By the end of the year, the market hierarchy was clear: PERC 182 cells had dropped to 0.275 yuan/W, while TOPCon 182×210 cells were leading the way at 0.265 yuan/W — even lower than some P-type counterparts.

Downstream demand constraints exacerbated the price pressure. Slower-than-expected investments in PV plants and a backlog of module inventory limited cell procurement, creating a buyer’s market in which manufacturers competed fiercely on price. By late June, some cell producers were quoting near-record lows, with competition devolving into a race to the bottom. The writing was on the wall: N-type cells were not just a niche product, but the future of the industry. Their rapid price convergence with P-type cells marked an irreversible shift.

Modules: A Deepening Price War and the Sector’s Darkest Hour

The module segment entered 2024 on the back of a downward trend that began in late 2023, but the year would see an all-out price war escalate. January data painted a stark picture: PERC 182 monofacial modules were priced at 0.908 yuan/W, while N-type TOPCon 182 bifacial modules commanded a premium at 0.975 yuan/W. Even HJT 210 bifacial modules, despite their efficiency advantages, struggled to maintain a price of 1.218 yuan/W in an increasingly cost-driven market.

As the year progressed, the decline became relentless. By December, PERC 182 monofacial modules had plummeted to 0.660 yuan/W, PERC 210 modules to 0.670 yuan/W and N-type TOPCon 182 bifacial modules to 0.710 yuan/W. The root causes were familiar: on the supply side, continuous capacity expansion in upstream sectors such as silicon materials and wafers created a surplus of raw materials, driving down production costs and, consequently, module prices. On the demand side, although the global PV market continued to grow, this growth failed to keep pace with the surge in supply. This left module manufacturers competing for a limited pool of orders.

The consequences were severe. Profit margins evaporated and the sector entered what many described as its ‘darkest hour’. Even N-type modules, despite their technological superiority, were not immune, as the market’s sole focus on price meant that efficiency gains were overlooked. Module enterprises faced a dual challenge: navigating the immediate price war while investing in R&D to stay ahead of technological shifts. Survival depended on maintaining a delicate balance of cost control, preserving market share, and fostering long-term innovation.

Inverters: A Beacon of Resilience Amidst Industry Turbulence

Amidst the industry’s widespread challenges, the inverter segment emerged as a rare bright spot in 2024, demonstrating remarkable resilience. Sungrow, the global leader, reported revenue of 77.86 billion RMB (an increase of 7.76% year on year) and a net profit of 11.04 billion RMB (an increase of 16.92%), having shipped 147 GW of PV inverters worldwide. Its energy storage business was a particular success, growing by 40.21% year on year to account for 32.06% of total revenue, which is evidence of the company’s successful diversification.

Deye crossed the 10 billion RMB revenue threshold for the first time, and Sineng Electric’s net profit surged 47% year on year to 419 million RMB, driven by a 69% increase in overseas revenue. These success stories stood in stark contrast to peers such as GoodWe, which posted a loss of 62 million RMB, and SolaX Power, whose net profit nosedived by 80.88%. This highlights a key fact: companies that prioritise technological innovation, overseas market expansion and product diversification thrive, while those that are overly reliant on domestic markets or slow to adapt struggle.

Industry-Wide Losses and the Path to Rejuvenation

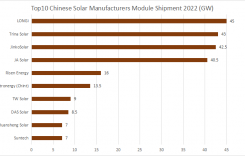

The cumulative effect of the 2024 price crisis was staggering: across the PV value chain, from silicon material to modules, enterprises reported massive losses. CNE Media’s incomplete statistics showed the number of PV enterprises filing for bankruptcy surpassing 100, with unregulated cross-sector capacity expansion identified as a key culprit. The industry found itself trapped in a vicious cycle of Pyrrhic victories, where short-term market share gains came at the expense of long-term sustainability.

Yet amid the red ink, a narrative of strategic resilience emerged. Leading firms like GCL, LONGi, and JA Solar shifted focus from price wars to R&D-driven differentiation. GCL doubled down on granular silicon, LONGi invested in BC technology, and TOPCon leaders pushed conversion rates to new heights. These companies recognised that short-term losses were a necessary investment in technological fortresses that would safeguard the industry’s future.

The crisis also laid bare a fundamental divide between “copycat” firms focused on quick profits and true innovators committed to long-term R&D. The latter group, though punished by short-term market sentiment, were building the capabilities needed to lead the next wave of PV technology—from N-type dominance to perovskite tandems and smart O&M systems. As the industry enters a new phase of development, the metrics that matter are shifting: R&D intensity, technological roadmaps, and ecosystem collaboration now outweigh short-term financial performance.

Looking ahead, breaking the cycle of price competition through stronger IP protection, policy support and industry self-discipline is key to recovery. Despite their losses, China’s PV powerhouses have demonstrated remarkable cost control and brand resilience, positioning them to lead the industry out of the trough. While 2024 was a painful year, it also provided a necessary reckoning that could ultimately forge a more sustainable, innovation-driven future for China’s PV industry on the global stage.