PVTIME – The US Section 201 tariff on solar products officially expired on 6 February 2026, bringing an eight-year period of trade protection to a close. First introduced under the Trump administration and subsequently extended, this policy has now ceased to apply, thereby removing an additional trade barrier for imported solar goods.

The tariff originated in May 2017, when the US solar company Suniva filed a petition with the International Trade Commission (ITC) calling for a Section 201 investigation into imported crystalline silicon solar cells and modules. Suniva claimed that a surge in imports had caused material injury to the US domestic industry, and all four ITC commissioners later reached an affirmative injury determination. They proposed relief measures centred on tariff quotas.

On 23 January 2018, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) announced the president’s approval of the ITC’s recommendations. From 7 February that year, a four-year Section 201 tariff was imposed on all imported solar cells and modules. This started at 30% in the first year, with a tariff quota exempting the first 2.5 GW of imported cells, and then decreased annually. Initially exempt were bifacial solar modules, which were then the mainstream product in the high-end photovoltaic market, a move that boosted their imports and weakened the tariff’s effectiveness. In September 2020, the US revoked this exemption and increased the tariff rate for 2021 from 15% to 18%, in an attempt to strengthen protection.

On 4 February 2022, the Biden administration extended the 201 tariff for another four years, setting rates between 14% and 15%. This followed an ITC recommendation in November 2021. This was intended to respond to demands from domestic manufacturers while balancing local industry protection with the energy transition. In February 2024, the ITC’s mid-term review noted that, while domestic solar manufacturing still faced import pressure, Inflation Reduction Act incentives had driven local investment growth.

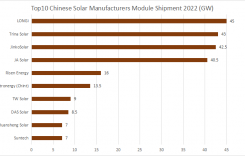

The tariff reshaped the global solar landscape. High costs suppressed US domestic demand, slowing global industry expansion. Meanwhile, Southeast Asia emerged as a key manufacturing hub, supported by Chinese enterprise capacity and the deepening of the global supply chain division of labour. US trade protectionism also prompted other nations to strengthen their own safeguards for the solar industry, indirectly intensifying global photovoltaic trade frictions.

In the long term, global solar competition will focus on technological innovation, cost control, and collaboration within the supply chain. The eight-year tariff experiment demonstrated that trade protectionism cannot shield the domestic industry, and that only open cooperation can drive sustained improvement. While the expiration of the tariff improves US market access for Chinese solar enterprises, they must remain vigilant about future frictions, boost R&D, refine their global strategy and consolidate their core competitiveness.

Currently, there has been no official announcement regarding new policies to replace the expired 201 tariff.

Scan the QR code to follow PVTIME official account on Wechat for latest news on PV+ES